This article was first published in November 2020 by Daily Cargo News.

I was invited by the American Bar Association (ABA) to prepare a chapter on the Australian sanctions regime for inclusion in an ABA publication on comparative sanctions regimes. As I provide advice on sanctions to clients and have an interest in my capacity as a director of the Export Council of Australia, it was a pleasure to accept and spend some time trying to reduce the complex issues both in Australia and overseas.

This article is timely as Australia’s sanctions regime has changed much in 2020, and by the time this article is published, further changes will have occurred with the establishment of a new portal.

Historical context

Sanctions have existed in one form or another as long as international trade has existed. They have become more of an issue since the establishment of the United Nations (UN) which adopted a “sanctions” regime to formalise the co-ordinated adoption of sanctions against countries, their governments or individuals. In many ways, they are the ultimate, approved international technical barrier to trade. Subsequently, nations and groups of nations have adopted their own form of sanctions for their own economic and political aims (think of the United States’ embargo on Cuba).

Sanctions change with the political landscape. The “new dawn” of the relaxation of global sanctions against Iran fell apart with the Trump administration. As a result, the United States (US) regime can still impact trade with Iran which had been “cleared” by Australian authorities – especially trying to get payments for goods and services from Iran when those payments involved banks or institutions having exposure to the US as it would be a risk. Which largely stops getting funding for trade with Iran or getting the proceeds of trade back to Australia.

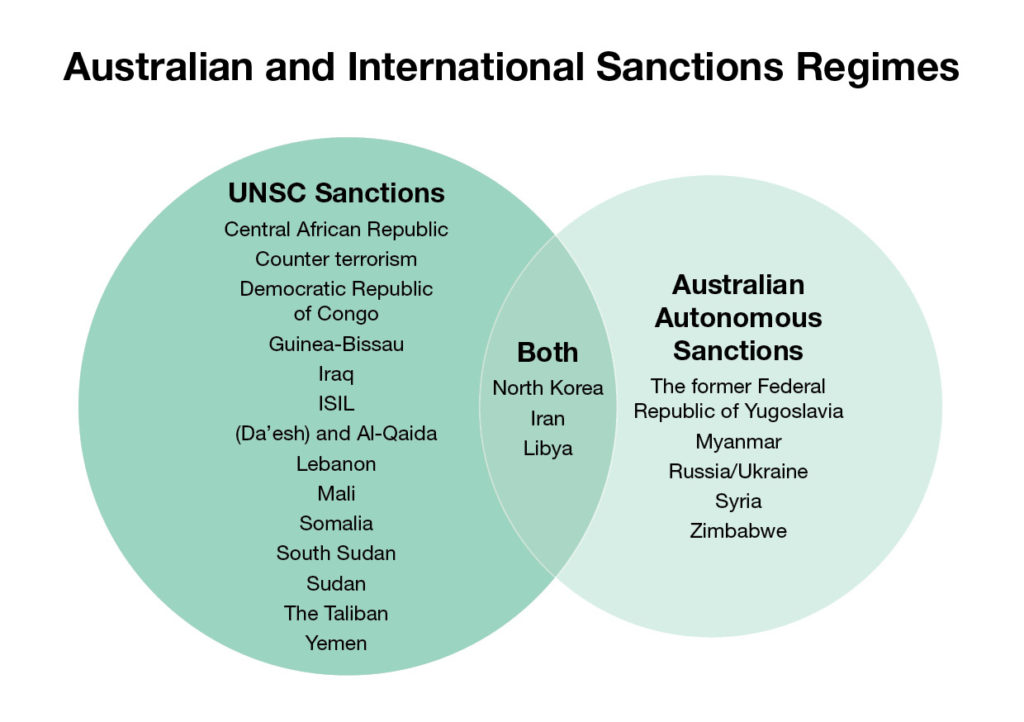

Source: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade Sanctions regimes.

Closer to home

Australia has, for some years, adopted a dual sanctions regime comprising both its adoption of the UNSC sanctions but also its own autonomous regime against certain countries, companies and individuals.

While the two systems often coincide in their operation, there are significant differences. This is reflected in separate legislation governing the impositions of sanctions whether under the United Nations Sanctions regime through the UN Act or our own autonomous sanctions regime under our Autonomous Act.

Of course, sanctions only form one part of export or import controls which need to be assessed by those involved in the international trade of goods and services as part of their self–assessment or due diligence in deciding to undertake the relevant endeavour. That includes the government’s Safeguard’s and Non-Proliferation Office, its counterterrorism and peacekeeping work alongside our Prohibited Imports and Exports Regulations which can change quickly.

The current COVID-19 pandemic itself has created its own separate set of controls around the export and import of personal protective equipment and related items required for the treatment of the pandemic.

A broad picture

The nature of the sanctions is deliberately broad. The UN Act, the Autonomous Act and the associated regulations and statutory instruments use the following common terms to describe sanction measures:

- making a ‘sanctioned supply’ of ‘export sanctioned goods’;

- making a ‘sanctioned import’ of ‘import sanctioned goods’;

- providing a ‘sanctioned service’;

- engaging in a ‘sanctioned commercial activity’;

- dealing with a ‘designated person or entity’;

- using or dealing with a ‘controlled asset’; or

- the entry into or transit through Australia of a ‘designated person’ or a ‘declared person’.

Under the Autonomous Act, the foreign affairs minister is granted broad executive powers in the administration of sanctions laws. Other agencies with administrative responsibilities include:

- The Department of Defence;

- Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT);

- The Defence Export Control (an agency within the Department of Defense);

- The Australian Federal Police;

- Australian Transaction Reports and Analysis Centre;

- Australian Securities and Investment Commissions;

- The Australian Border Force as a part of the Department of Home Affairs; and

- The Reserve Bank of Australia.

Ensuring compliance

Governments have put into place arrangements to ensure sanctions are not breached. In addition to the work of the government and its agencies, the federal government has provided its own resources to those seeking confirmation on its proposed transactions. This has included the maintenance and revision of the Consolidated List which DFAT describes as “a list of all persons and entities who are subject to targeted financial sanctions under Australian sanctions law. Those listed may be Australian citizens, foreign nationals, or residents in Australia or overseas”.

The government had also maintained an online mechanism for those seeking approval for its dealings originally through specific divisions in DFAT in conjunction with the previous Online Sanctions Administration System (OSAS) which is soon to be replaced. However, the regime has not remained in the same form as was originally established.

From 1 January 2020, the Australian Sanctions Office (ASO) became the Australian government’s sanctions regulator. According to DFAT, the ASO provides guidance to regulated entities, including government agencies, individuals, business and other organisations on Australian sanctions law. It also processes applications for, and issues, sanctions permits and works with individuals, business and other organisations to promote compliance and help prevent breaches of the law.

The ASO works in partnership with other government agencies to monitor compliance with sanctions legislation; and supports corrective and enforcement action by law enforcement agencies in those cases of suspected non-compliance.

The ASO sits within DFAT’s Legal Division. As a result, the administration of the sanctions laws and regulations is undertaken by DFAT. This has been only one part of the reforms as the government has been working on a new electronic portal to deal with sanctions issues, which was launched on 1 October 2020. Known as Pax (Latin for “peace”) the new portal will replace the OSAS.

Final thoughts

There is little question that we welcome the new arrangements and trust that Pax and its processes will aid in facilitating trade. It will be important to those involved in international trade to be aware of the sanctions regime and secure appropriate approvals and permits as breaches of the legislative provisions lead to heavy penalties. It also is hoped that Pax will be designed so as to interact with any new international trade portals designed by governments, even, one day, into a single window for trade.

For further advice on any questions you may have, please contact our Customs & Trade team for further advice.

| Disclaimer: This publication contains comments of a general nature only and is provided as an information service. It is not intended to be relied upon as, nor is it a substitute for specific professional advice. No responsibility can be accepted by Rigby Cooke Lawyers or the authors for loss occasioned to any person doing anything as a result of any material in this publication.

Liability limited by a scheme approved under Professional Standards Legislation. ©2020 Rigby Cooke Lawyers |